The Teacher Retirement System of Texas Board of Trustees at a meeting in August, where officials discussed the fund’s “unsound” accounting status, resulting from years of low investment returns.

Few people remember the exact events that led some 1.5 million Texas public-school teachers to invest a big chunk of their retirement savings in a Turkish steel company now in the crosshairs of President Donald Trump.

But it all dates back to a warm, overcast day in February 2007, in the wine-country town of Fredericksburg. There, in an airport conference center styled to look like a World War II-style Quonset hut, Texas officials made the historic decision to pump nearly 10% of the state’s biggest public pension fund, the Teacher Retirement System, into stocks from risky places like Brazil, Russia, India, China, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey.

Such “emerging-market” stocks are considered highly speculative, even by professional investors, because the countries often have authoritarian governments, widespread corruption, fledgling markets, volatile currencies and more tumultuous economies when compared with markets in the U.S., Europe and Japan. The tradeoff, at least according to the Teacher Retirement System’s then-chief investment officer, a former hedge-fund executive named Thomas Britton “Britt” Harris, was that the riskier investments would bring bigger rewards – and a bigger payoff for the teachers.

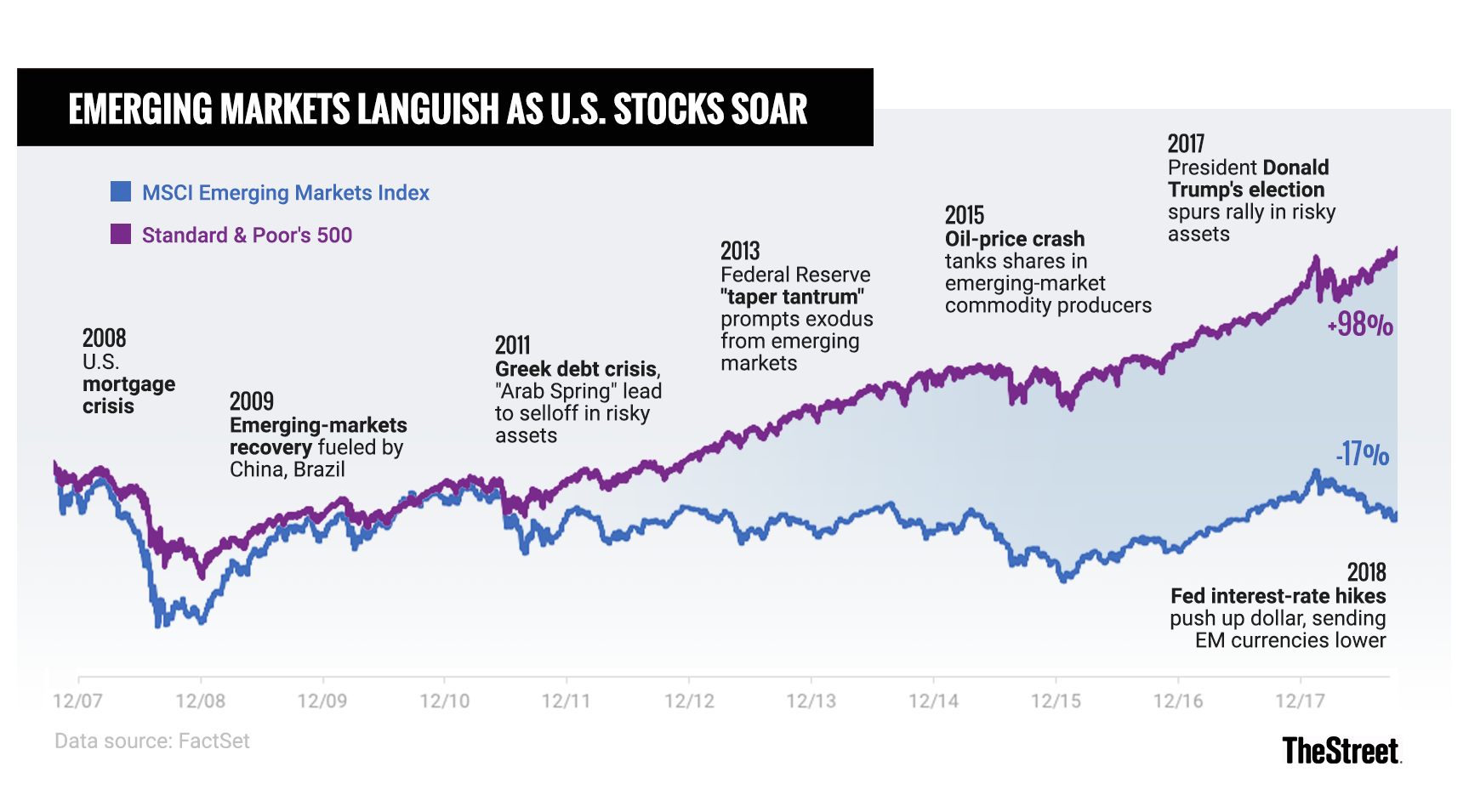

It hasn’t worked out that way. Over the past decade, emerging-market stocks have produced investment returns averaging just 1.1% per year, well below the Texas fund’s overall target of 8%, and a fraction of the 11% average return projected by state officials back in 2007.

Partly as a result, the fund became actuarially unsound – an accounting designation that means teachers probably will have to increase their required monthly contributions to keep the retirement system solvent. Ironically, had the trustees instead simply kept the money in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of large U.S. stocks, they would have reaped returns averaging 8.9% per year, or more than more than enough to put the pension fund back onto a sound footing.

“Taking that risk was not a good thing,” says Stephen Nesbitt, CEO of Marina del Rey, California-based Cliffwater LLC, which advises pension funds and foundations on investments. “In hindsight, anything non-U.S. has not been particularly smart.”

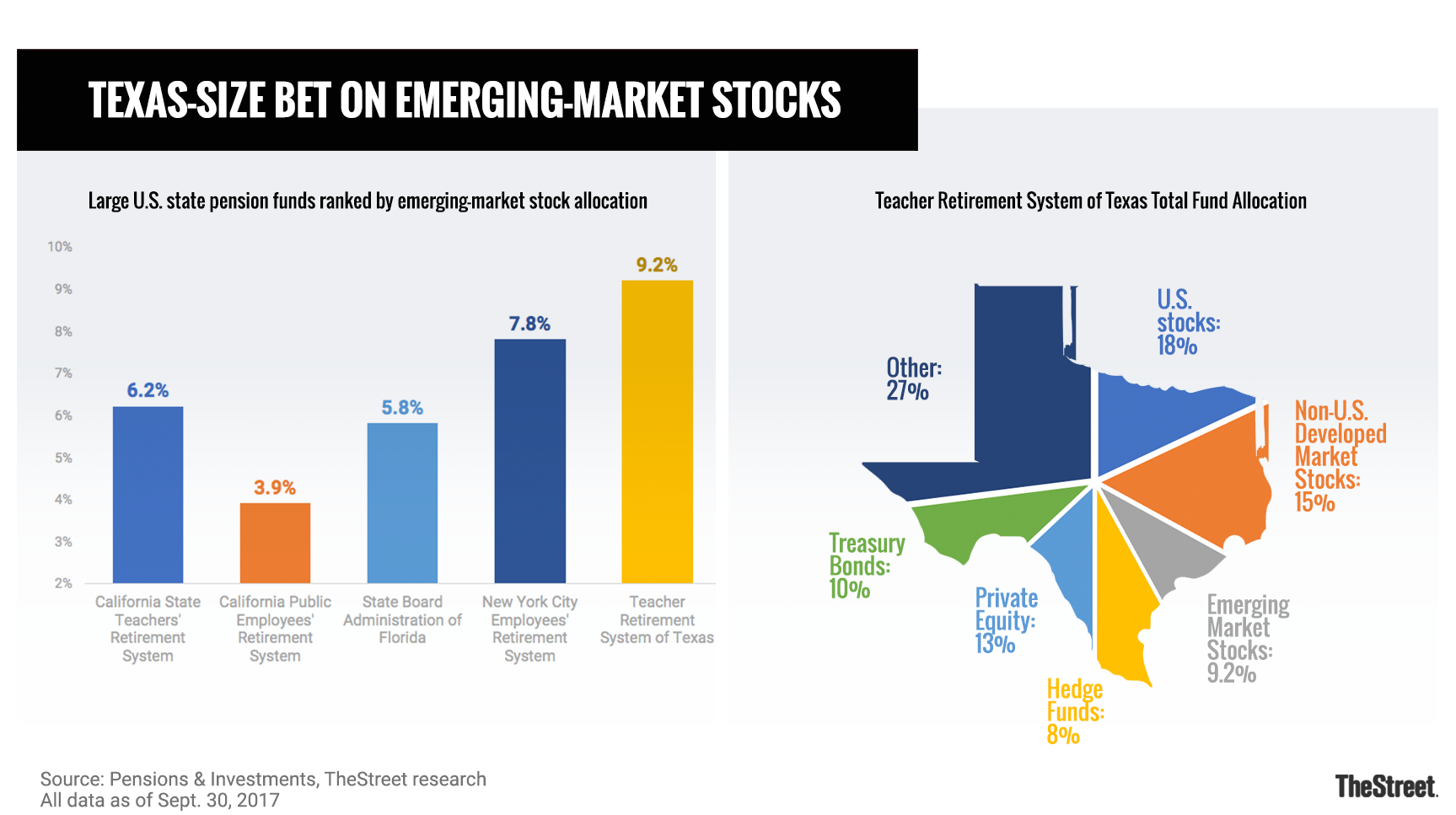

The Teacher Retirement System isn’t the only public pension fund that loaded up on emerging-market stocks in search of higher returns, based on a review of public reports, meeting transcripts and government documents obtained through open-records requests. Funds in New York, Connecticut, California and other states also dove in, convinced that rapid economic growth in less-developed countries would bring superior returns, and that the third-world debt crises of prior eras had faded into the past.

The Teacher Retirement System isn’t the only public pension fund that loaded up on emerging-market stocks in search of higher returns, based on a review of public reports, meeting transcripts and government documents obtained through open-records requests. Funds in New York, Connecticut, California and other states also dove in, convinced that rapid economic growth in less-developed countries would bring superior returns, and that the third-world debt crises of prior eras had faded into the past.

But the Teacher Retirement System’s decision to pump almost 10% of its assets into emerging-market stocks amounted to a bold, Texas-sized bet. As of March 31, the fund held about $13.8 billion of emerging-market stocks, the highest allocation on a percentage basis among U.S. public retirement plans, according to the publication Pensions & Investments. Even the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the nation’s largest public pension fund, has kept its allocation to the asset class at a trim 4%.

Charts showing the relative size of the emerging-market stock portfolio held by the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

In hindsight, the dismal returns from emerging-market stocks over the past decade show that the Texas fund’s strategy was a big mistake. And the portfolio is poised to rack up additional losses this year, with stocks from China to Turkey falling due to major shifts taking place in global markets: A key index of emerging markets is down 12% this year, while the S&P 500 has gained 12%.

One key handicap for the Teacher Retirement System is structural: Professional investors can rush in and out of emerging-market stocks when market sentiment shifts. But a giant, public, bureaucratic fund like the one in Texas – now at $150 billion in assets – can’t so easily bob and weave.

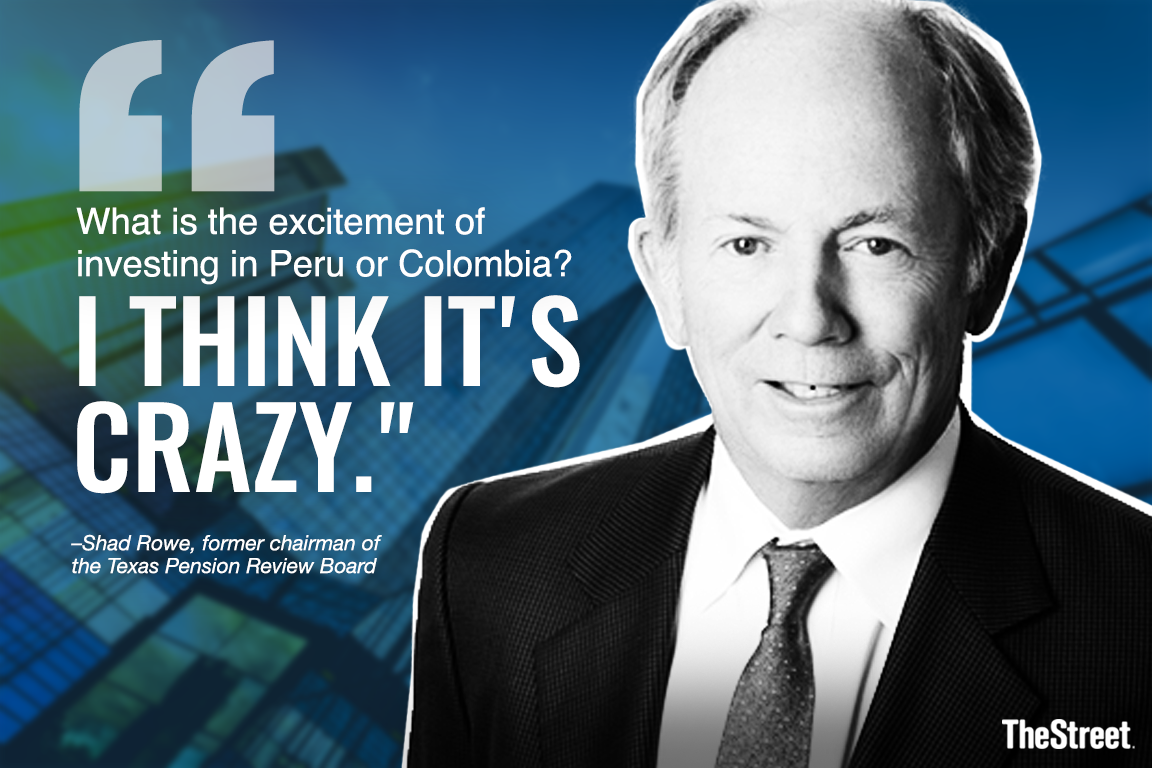

Shad Rowe, a Dallas-based investor who previously served as chairman of the Texas Pension Review Board, which oversees the state’s retirement systems, said in a telephone interview that it boils down to good-old Texas common sense: A state-run pension fund set up to invest teachers’ retirement savings shouldn’t be making big stock bets in risky foreign countries.

Corporate standards are higher in the U.S., with strict accounting rules, ample disclosure, prohibitions against conflicts of interest, watchful compensation policies and vigilance against corruption, Rowe says. What’s more, many large U.S. companies already have operations in emerging markets, so investors can get exposure to the countries simply by buying the S&P 500, he says.

John-Paul Smith, a former Deutsche Bank analyst who correctly predicted Russia’s stock-market crash in 1998 and now runs his own emerging-market analysis firm in London, says that the U.S., Europe and Japan have capital markets and democratic societies that foster and reward innovative and disruptive companies like Alphabet Inc. (GOOGL – Get Report), Amazon.com Inc. (AMZN – Get Report) and Apple Inc. (AAPL – Get Report) .

“The U.S. is the place to be, because of the rule of law,” Rowe said in a telephone interview. “At least you have some chance of succeeding. We cash our checks here. We do our business here. What is the excitement of investing in Peru or Colombia? I think it’s crazy.”

Trump’s threats to impose steep tariffs on imports from China have prompted many big investors to pull their money out of the Asian country, weakening its currency versus the U.S. dollar. A years-long corruption probe in Brazil has thrown the country’s politics into disarray, while Russia is suffering under sanctions stemming from its occupation of Crimea, alleged interference in U.S. elections and, more recently, the attempted poisoning of an ex-spy in Britain. Mexico has lost some allure in the eyes of pro-business investors for the election of a leftist president last month – in turn partly triggered by an anti-Trump backlash among Hispanic voters.

The U.S. Federal Reserve’s steady push to raise interest rates has increased yields on U.S. assets like Treasury bonds, making many big investors less keen on putting money into risky foreign countries. As they’ve brought that capital back to the U.S., the dollar has surged, which by definition means that other countries’ currencies have fallen. It’s a value-killer for investors in foreign stocks.

And then there’s Turkey, the latest poster child for an emerging-market meltdown. The increasingly authoritarian President Recip Tayyip Erdogan has condemned rising interest rates, a key monetary-policy tool that’s typically used to push back against rampant inflation and a tumbling currency.

The country’s exchange rate and stocks took another hit recently, when Trump doubled tariff rates on imported steel from Turkey over the country’s detention of American pastor Andrew Brunson.

As part of its portfolio of emerging-market stocks, the Teacher Retirement System has been a big investor in Erdemir for the past decade. This year alone, the company’s shares have tumbled about 29% in dollar terms.

Rob Maxwell, a spokesman for the Teacher Retirement System, wrote in an e-mail that the goal of investing so much in emerging-market stocks was to “improve the return of the trust at the same or lower risk.” Over the decade through August 2008, he noted, the stocks had returned an average 18% per year, and the trust’s investment partners expected them to continue to outperform the U.S. market.

“With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that many were proved wrong, in that the U.S. outperformed emerging markets,” Maxwell said in the e-mail.

The Teacher Retirement System’s chief investment officer, Jerry Albright, declined to sit for an interview, according to Maxwell.

Jerry Albright, chief investment officer of the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

Jerry Albright, chief investment officer of the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that Wall Street analysts started touting emerging-market stocks in the early 2000s, just after the crash of the high-flying dot-com stocks they had once touted. The theory, promulgated by prestigious firms like Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (GS – Get Report) , was that less-developed countries would post faster economic growth over the coming decades than big, modern markets like the United States. Therefore, the stocks were bound to outperform.

Investment strategists pushed the idea that money managers should have diversified portfolios; and emerging-market stocks, the thinking went, would do well when U.S. stocks languished. It didn’t hurt that the stocks went on a hot streak in the mid-2000s, making them an easy sell for Wall Street brokers and a popular choice among the consultants who advise pension funds on their portfolios. Investors were dazzled by the powerhouse growth of China and India and fast fortunes made by showy tycoons in Brazil and Russia, and the pension-fund managers were no exception.

In 2007, JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM – Get Report) , the giant U.S. bank, told the Teacher Retirement System that the exotic stocks would produce long-term returns averaging 11.5% a year, the highest among 25 asset classes, according to documents prepared at the time by the pension fund’s staff. The banks, of course, would make fatter commissions from handling exotic international trades than they could make from slinging plain-vanilla stocks on U.S. exchanges.

Ask John Graham Jr., a Fredericksburg-based financial adviser, about his tenure as a trustee of the Texas fund from 2003 through 2009, and he quickly recalls the February 2007 meeting in his hometown – especially where the board had lunch that day: at his wife’s restaurant, Hondo’s on Main. The popular eating spot is known for its “Death Burger” — a mesquite-grilled, half-pound patty of beef, smothered in jalapeños, chipotle chilies and green onions, then served on a toasted sourdough bun with a mustard-mayonnaise mix on the side.

But in a phone interview, Graham said he barely remembers the deliberations over emerging markets.

“That was a long time ago,” Graham said. “I have gone on to other things.”

The risks of third-world investing have been well known for decades, based on the frequent booms and busts in the countries. In fact, according to a research paper from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2001, crises are happening nearly all the time.

There was the Mexican “tequila” crisis in 1994, the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the Russian ruble devaluation in 1998 and multiple debt defaults by Argentina over the past two decades . Brazil, Ecuador, Ukraine, Turkey and Uruguay also suffered economic crises during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But by the early 2000s, those lessons were all but forgotten. In 2001, the head of economics research for Goldman Sachs, Jim O’Neill, coined the acronym “BRIC” – Brazil, Russia, India, China – for economies projected to grow faster than places like the U.S., Europe and Japan.

According to the International Monetary Fund, emerging and developing economies now account for about 60% of global economic output, compared with just under half a decade ago.

Scores of Wall Street executives and analysts took up the narrative – especially as stock markets soared in China and Brazil. “The risk of investing in emerging markets has been falling over the last few years,” Mark Mobius, a Franklin Templeton money manager who’s considered one of the foremost experts on the topic, told Bloomberg in 2005.

The Teacher Retirement System was set up in 1937 to provide retirement payments to employees of the state’s public schools, colleges, and universities. Since then it has expanded to about 1.5 million members from 38,000. Based on assets under management, it ranks among the 10 biggest public pension funds in the U.S. (Full disclosure: This reporter’s spouse is a University of Texas employee and thus a participant in the retirement system.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the giant pension plan is a major Wall Street client, with assets rivaling those of the world’s biggest hedge funds.

In the decade through 2006, the Texas fund had used a conservative mix of domestic stocks, bonds and cash to produce 9.2% annual returns on average – plenty enough to meet the 8% target.

But in the mid-2000s, then-Governor Rick Perry, now Trump’s energy secretary, decided he wanted a “world-class manager” who could bring the retirement system into the modern era of investing, with blossoming asset classes like private equity, hedge funds and, yes, emerging markets, says James Lee, a Houston-based investor who served at the time as a trustee and later chairman of the board.

Other big pension funds, like those in California and New York, were pushing into sexier investing frontiers, and the Texas fund didn’t want to be left behind.

Britt Harris, the Teacher Retirement System’s former chief investment officer.

Enter Harris, 60, a former CEO of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s biggest hedge fund.

In the universe of pension investing, Harris was a superstar, having served as chief of Verizon Communications’ plan, overseeing the retirement savings for telephone-system workers and other employees of the utility. While at New York-based Verizon, he had a $40 billion-plus pot of money to farm out, allowing him to befriend some of Wall Street’s biggest names. He allocated at least $1.2 billion to Bridgewater and meted out more than $2.5 billion to Morgan Stanley – so much that the investment bank even quoted Harris in its annual report for 2003.

He’s the only pension-fund executive on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s prestigious Investor Advisory Committee on Financial Markets, which also includes hedge-fund titans like Bridgewater Chairman Ray Dalio and Paul Tudor Jones, chief investment officer of Tudor Investment Corp.

So when the Teacher Retirement System suddenly had an opening for a new chief investment officer in 2006, Harris shot to the top of the list, ahead of internal candidates. It didn’t hurt that he was a Texas native, the son of a public-school teacher and an alumnus of Texas A&M University, Perry’s alma mater.

Harris stepped into the post in December 2006 and immediately set about making changes – and taking bigger risks.

He argued that the Texas plan needed to diversify its portfolio; too much money was parked in U.S. stocks and bonds, according to documents and meeting minutes obtained through requests made under the state’s open-records law. In board meetings, Harris argued that the strategy was behind the times, and that it would only produce a projected long-term return of 7.6%, hardly enough to meet the pension fund’s 8% target.

The trustees, given their lack of high-finance backgrounds, were ill-equipped to push back. They included three school superintendents, a small-town financial adviser, a retired University of Texas power-plant operator, a rancher, a Houston-based lawyer and two private investors.

“Before we hired Britt Harris, we used to be very involved in making decisions,” says Philip Mullins, the power-plant operator, who has since retired from the board. “But when he came on, the board stopped being hands-on. We knew that he was doing something different.”

So in early 2007, starting with the meeting at the Fredericksburg airport, Harris revealed his plan to shake up the Texas fund with a new blend of assets that had gone untouched in the past – to a large part because they had been deemed too risky. Harris’s team, along with its outside investment consultants from the firm Aon Hewitt Ennis Knupp, created a new asset-allocation plan designed to produce a long-term expected return of 8.7%.

Key to the plan was sharply reducing the fund’s holdings of U.S. stocks and bonds and putting about 10% of the portfolio into hedge funds, 10% into private equity, 10% into real estate and 10% into emerging markets. While each category was risky on a standalone basis, the theory was that lumping them all into the portfolio would diversify the risk, while boosting long-term returns.

“Any investment professional would have told you we needed more exposure to the EM asset class,” said Lee. He resigned from his post at the Texas fund in 2009 after it was reported that he had a judgment against him in Nevada for $110,000 of unpaid gambling debt, according to the Houston Chronicle.

He now runs the Patriot Fund, a mutual fund that steers clear of companies with business ties to Iran, Syria and Sudan, since they’re designated by the U.S. Department of State as sponsors of terrorism.

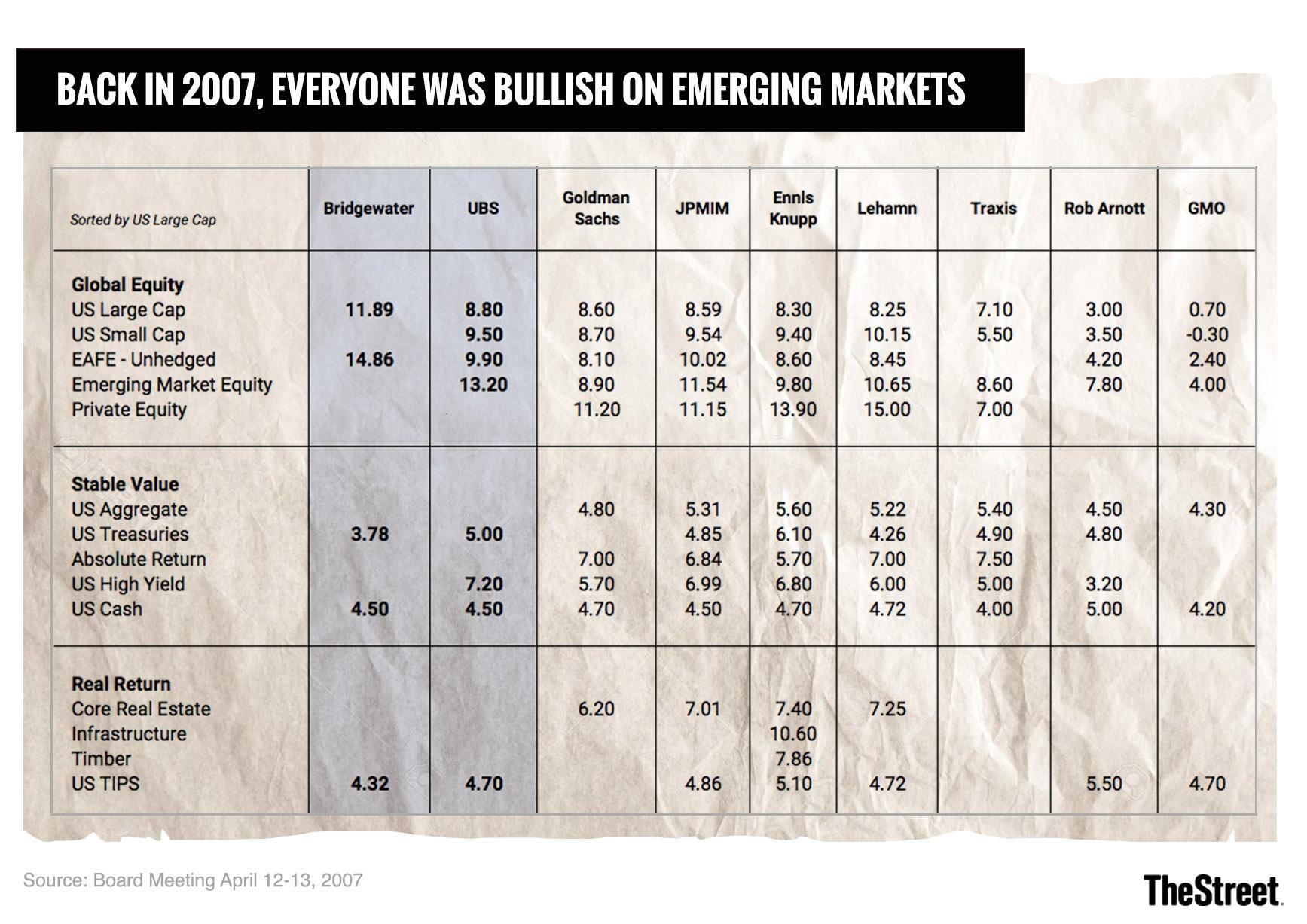

Harris showed the trustees hundreds of pages of documents ranking various asset classes by their projected future returns. He solicited estimates from the biggest names in finance: JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, the Swiss bank UBS AG, even the now-defunct Wall Street firm Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. They all put emerging markets at or near the top of the list.

The takeaway? By making Harris’s recommended changes, the pension fund would easily surpass its 8% target return.

Harris also solicited input from Research Affiliates Chairman Rob Arnott, a well-known investment strategist and money manager in Newport Beach, California. Arnott projected returns of 7.8% for emerging-markets, the highest among nine rated asset classes, fund documents show.

In a phone interview, Arnott said he submitted the projections as a favor to Harris. But he said he never would have recommended that a big public pension fund like the Teacher Retirement System take such a massive stake in emerging-market stocks – due to the historically large swings in their value.

“I was not a bull on emerging markets at the time,” he said. “My view was that the long-term returns over a 10- to 20-year horizon would probably be OK, but not brilliant for the volatility involved.”

Photo of a 2007 Teacher Retirement System document showing Wall Street firms’ projections for future returns from emerging-market stocks.

According to minutes of board meetings that year, trustees debated the merits and risks of hedge funds, private equity and real estate. But little discussion was devoted to emerging markets.

“I remember very little about it,” Jarvis Hollingsworth, a Houston-based lawyer who served at the time as chairman of the pension fund’s board of trustees, said in a phone interview in 2015. Earlier this year, he started a new term as chairman.

Yet even those who back the philosophy of portfolio diversification argue that the Texas fund went overboard.

James Hille, who preceded Harris as the fund’s chief investment officer before leaving in early 2006 to run Texas Christian University’s $1.2 billion endowment, says the magnitude of the emerging-markets bet surprised him when he heard about it. In the early 2000s, he had advocated for the Teacher Retirement System to buy emerging-market stocks. But because of the risk, he says, he didn’t think they should ever represent more than 2% to 3% of total assets.

“If you look at emerging markets, they giveth and they taketh away,” Hille said in a phone interview. “The story of growth — that that’s where the world’s growth is. Well, that’s true for a period. But just like any story that has a lot of growth, it has a finite life to it.”

In October 2007, the Texas pension fund sold $8.7 billion of U.S. stocks and used about half of the proceeds to buy emerging-market stocks.

The trade was exactly what Harris wanted, but it didn’t go as well as planned. During the prior month, in September 2007, emerging-market stocks had surged 8%. According to a person with knowledge of the matter, some executives inside the pension fund suspected that Wall Street traders were buying in advance of the Texas-size order.

It was unavoidable, really, since big state pension funds must operate in the public eye. After all, during public meetings and in easily accessible reports, the Teacher Retirement System had tipped its plan to buy a giant slug of emerging-market stocks, which often are so thinly traded on their local-country exchanges that prices can be pushed up or down by a big buyer or seller.

The Wall Street firms stood to benefit grandly from handling the big order for foreign stocks. In 2012, the Teacher Retirement System paid an average 8.3-cent commission to international brokerage firms, roughly four times the rate paid to U.S. firms, according to an annual report that year.

For Harris, though, it was time to celebrate. He had successfully retooled the Texas fund’s portfolio to his liking – and ratcheted up the risk.

In early 2008, just months before the subprime mortgage crisis nearly led to the collapse of the entire U.S. financial system, Harris hosted a dinner at Fleming’s steakhouse in Austin, attended by Perry as well as Lehman Brothers CEO Dick Fuld, Morgan Stanley CEO John Mack and Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest money manager. Under Harris’s direction, Teacher Retirement System had named the three firms, along with JPMorgan, as “strategic partners,” a program in which each firm would be paid to manage $1 billion of the fund’s money and in return provide free advice on investment strategy.

“Britt was holding court,” remembers Ronnie Jung, a former executive director of the Texas fund, who attended the dinner.

In hindsight, the Texas fund would have been hard-pressed to more perfectly time the emerging-markets peak. As U.S. subprime mortgage defaults mounted in 2008, wiping out more than $1 trillion of the value of mortgage-backed securities that had been sold by Wall Street during the housing boom, investors did what investors often do when there’s a crisis: They sold their riskiest assets and bought U.S. Treasuries.

Those included emerging-market stocks – undermining the premise that non-U.S. assets would help to diversify a portfolio. Even though the crisis had started in the U.S., the MSCI Emerging Markets Index – the asset category’s main performance benchmark — plunged 55% in 2008, far exceeding the S&P 500’s loss of 38% that year.

By August 2009, the Teacher Retirement System had lost so much money that its unfunded liabilities – obligations minus assets – climbed to almost $40 billion from $3.5 billion two years earlier, according to an annual report.

Harris was undaunted. According to minutes of a board meeting that year, he told trustees that emerging-market stocks, now even cheaper, were among the best opportunities around. He reemphasized the importance of diversification. The minutes show no dissent from trustees.

So they let it ride.

Harris quit the Texas pension fund earlier this year to take another job as chief investment officer for the University of Texas Investment Management Co., also based in Austin. Harris declined to comment through a University of Texas System spokeswoman, Karen Adler.

Yet the teachers are still holding onto the legacy of the emerging-market stocks.

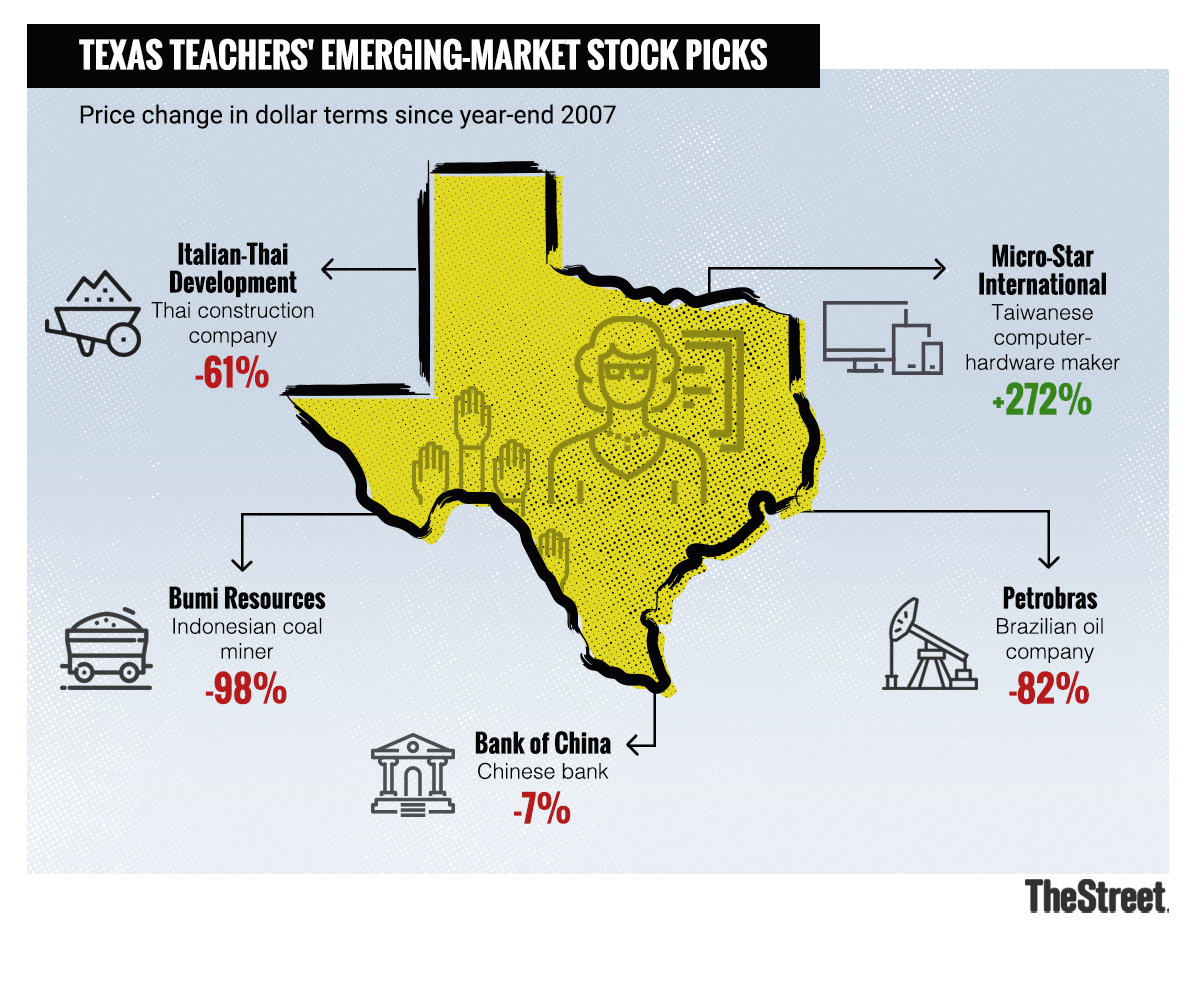

A sampling of the emerging-market stocks held by the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

According to documents obtained through open-records requests, the Texas fund’s emerging-market stock holdings at the end of 2007 included Bank of China, which has been roughly flat in dollar terms since then; Bumi Resources, an Indonesian miner, which has since fallen 97%; Italian-Thai Development, a construction company in Thailand, down 65%; and Petrobras, the Brazilian national oil producer, down 81%. There were some winners, of course: Micro-Star International, a Taiwanese computer-hardware maker, quadrupled during the period.

And don’t forget Erdemir, the 53-year old Turkish company that is now a part of OYAK Mining Metallurgy Group, the country’s largest integrated steel producer. According to an annual report, the parent company is one of Turkey’s biggest employers, with 12,000 employees and net sales of $5.1 billion in 2017, on par with medium-size U.S. companies like videogame-software-maker Electronic Arts Inc. EA and restaurant chain Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. CMG.

At the end of 2007, the Texas fund owned 865,000 of Erdemir’s shares, valued at about $1.8 million, documents show. The stock price plunged during the financial crisis of 2008, but it later rebounded and ultimately quintupled from 2009 through 2017. At that point, according to the documents, the Teacher Retirement System sold the majority of its stake, locking in big profits.

Earlier this year, the documents show, the Texas fund’s managers tiptoed back in, amassing 2.2 million shares, worth about $5 million at the end of June. They’ve fallen about 50% in dollar terms since then.

The Texas fund’s foray into emerging markets still puzzles Terry Ellis, a South African-born investor and horsebreeder who served as board chairman in the years prior to Harris’s arrival. Putting nearly 10% into the asset class is “way too much,” he argues. Had he remained chairman, he says, he would have tried to stop it.

“It’s all sexy until it isn’t,” Ellis said in a phone interview from his new home in Florida. “It’s damn risky, by definition. Just talk to the people in Argentina and Venezuela. Even if you tempered your word ‘risky’ and used the word ‘volatile,’ putting 10% of your assets into one of the most volatile areas you can invest in, to me, just doesn’t make sense.”