On a crisp, fall day in Santa Ana, California, Mary Acosta Rodriguez Martinez Garcia steps forward gingerly, leaning on her cane as she walks to the spot along the railroad tracks that intersect with Santa Ana Boulevard. This is where her grandfather’s house once stood, before it was swallowed whole by the expansion of the boulevard that today leads into the heart of Santa Ana’s downtown and the Orange County Civic Center. Like her grandfather’s home, where she lived most of her childhood, most of the landmarks from her formative years during the 1940s and 1950s — the places and buildings that she cherished the most from her youth — have long disappeared.

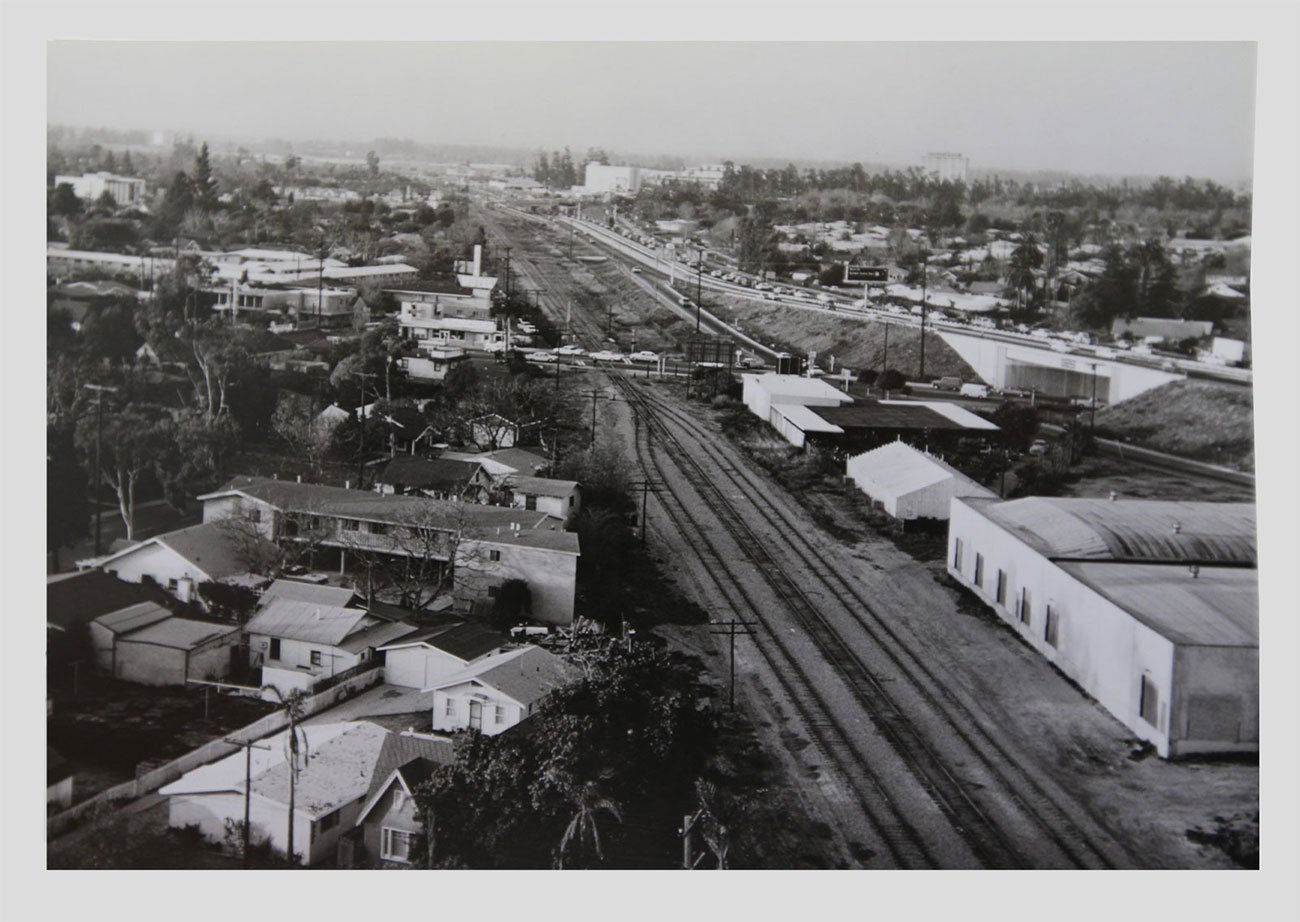

Surrounding orange groves, walnut and apricot orchards gave the Logan barrio, one of Santa Ana’s oldest neighborhoods, a pastoral atmosphere throughout Garcia’s childhood. But the barrio was also squeezed between two railroads on its eastern and western boundaries. The neighborhood was originally settled by European Americans, and as they moved out, Mexican and Mexican American residents moved in. Many of them, like Garcia’s uncles, worked the orchards harvesting oranges, or in packing houses, sorting the fruits of Orange County’s citrus and walnut trees.

During the early part of the 20th century, trains hauled goods ranging from citrus to lumber out to destinations across the country. But by the middle part of the century, as the city welcomed industry, the goods reflected the new businesses that the city allowed into the neighborhood and throughout the eastside of Santa Ana: among them oil, petroleum, aviation gasoline, lead ore, metals, chemicals, fertilizers, and herbicides.

Insurance maps created by the Sanborn Map Company between 1920 and 1960 show that the area surrounding Logan’s residential core, known as the Greater Logan Area, included fossil fuel companies that stored their oil and gasoline in steel tanks above ground. One oil depot was located near the home of Garcia’s grandfather. As a child Garcia recalls jumping over slick oil puddles in the alley on her way to school. “We just thought it was part of living there,” Garcia, now 78 years old, told Grist. “I mean: Doesn’t everybody live near where there’s oil on the ground?”

An industrial business, left, bordered by barbed wire, presses against the yard of a home in the Logan neighborhood, where Grist found hazardous levels of soil lead contamination. Grist / Daniel A. Anderson

An industrial business, left, bordered by barbed wire, presses against the yard of a home in the Logan neighborhood, where Grist found hazardous levels of soil lead contamination. Grist / Daniel A. AndersonHeavyweight businesses like Standard Oil Company, General Petroleum Corporation of California, and Shell Oil Company shared the neighborhood with a foundry, a lead smelter and battery recycling facility, and a liquid fertilizer company. Garcia wonders whether the fact that so many of her family members lived with asthma was connected to the pollution that came with those firms and facilities. “Nowadays you wouldn’t have that,” said Garcia. But her relatives never complained. They were grateful, given the poverty in which they were raised, to have homes and jobs to support their families. Her grandparents used to repeat a Mexican saying: “Los Estados Unidos para vivir, y México para morir” — in the United States they could live prosperously by working hard, and then return to Mexico to die in peace.

Today, there is scant physical evidence that these businesses from Garcia’s era existed, and if you attempt to paint a picture of industrial pollution in Santa Ana using even the most rigorous governmental data, you wouldn’t conclude that the city — and Logan, in particular — is hazardous. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxic Release Inventory, a database that catalogs 35 years of site-specific pollution, shows 99 distinct entries in Santa Ana since the program’s inception. Only one, a chemical company, borders the Logan barrio.

A Grist analysis of historical business directories, however, offers a different view. Most states, including California, have published directories documenting industrial businesses since the mid-20th century, listing addresses, products produced, and number of employees, among other data points. Borrowing methodology from the 2018 book Sites Unseen: Uncovering Hidden Hazards in American Cities, by sociologists Scott Frickel and James Elliott, Grist cataloged the accumulation of defunct industrial sites in these directories that have evaded the oversight of the EPA, often due to their age. California directories cataloging manufacturing businesses that Grist analyzed as far back as the 1960s describe nearly 2,000 such sites dotting Santa Ana’s urban landscape. More than 300 were active as of 2014, the most recent directory Grist analyzed. The other businesses — in industries like plastics, fabricated metals, and chemicals — might never have had their toxic footprints cleaned up. Indeed, some properties were merely rezoned for residential use.

Ongoing noise and pollution from industrial businesses like this one, seen from Logan resident Frances Orozco’s second floor window, have burdened residents for decades. Grist / Daniel A. Anderson

Ongoing noise and pollution from industrial businesses like this one, seen from Logan resident Frances Orozco’s second floor window, have burdened residents for decades. Grist / Daniel A. AndersonMapping these historic manufacturing sites, which Frickel and Elliott describe as “relic sites,” reveals a potential legacy of pollution. In the 92701 ZIP code, where Logan is located, only 19 industrial sites appear in the 2014 compendium. But almost 200 appear in the older directories. Neighborhoods like Logan, a historically segregated residential barrio that the city subsequently zoned as industrial in 1929, reveal exactly the problem that Frickel and Elliott discovered while researching the four cities in Sites Unseen: Minneapolis, Portland, New Orleans, and Philadelphia.

“Because these are small places — these are [like] little welding shops — so regulations don’t require them to report. There’s no records kept on these places,” Frickel told Grist. “They’re small, so they’re not heavily capitalized, so these people don’t have money to clean things up when there’s a problem.”

Small businesses like this auto repair shop co-mingle with apartment complexes and single-family homes in and around Santa Ana’s Logan neighborhood. Daniel A. Anderson

Small businesses like this auto repair shop co-mingle with apartment complexes and single-family homes in and around Santa Ana’s Logan neighborhood. Daniel A. AndersonIn their study, Frickel and Elliott tapped manufacturing directories dating as far back as the 1950s in those four cities and discovered that more than 90 percent of sites where hazardous industry (defined as businesses that perform work known to release toxic chemicals and heavy metals) has operated over the past half-century have become essentially invisible to regulatory agencies. One reason for this: The EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory Program doesn’t require businesses below a certain size to report emissions, so small polluters that go in and out of business relatively quickly are able to escape formal scrutiny.

“TRI data don’t begin to do justice to — or they don’t begin to render a historically accurate picture of — industrial activity and the contamination (and legacy contamination) that inevitably sticks around when those industries leave,” Frickel said, noting that Grist’s findings in Santa Ana underscore the shortcomings of government data for revealing contamination.

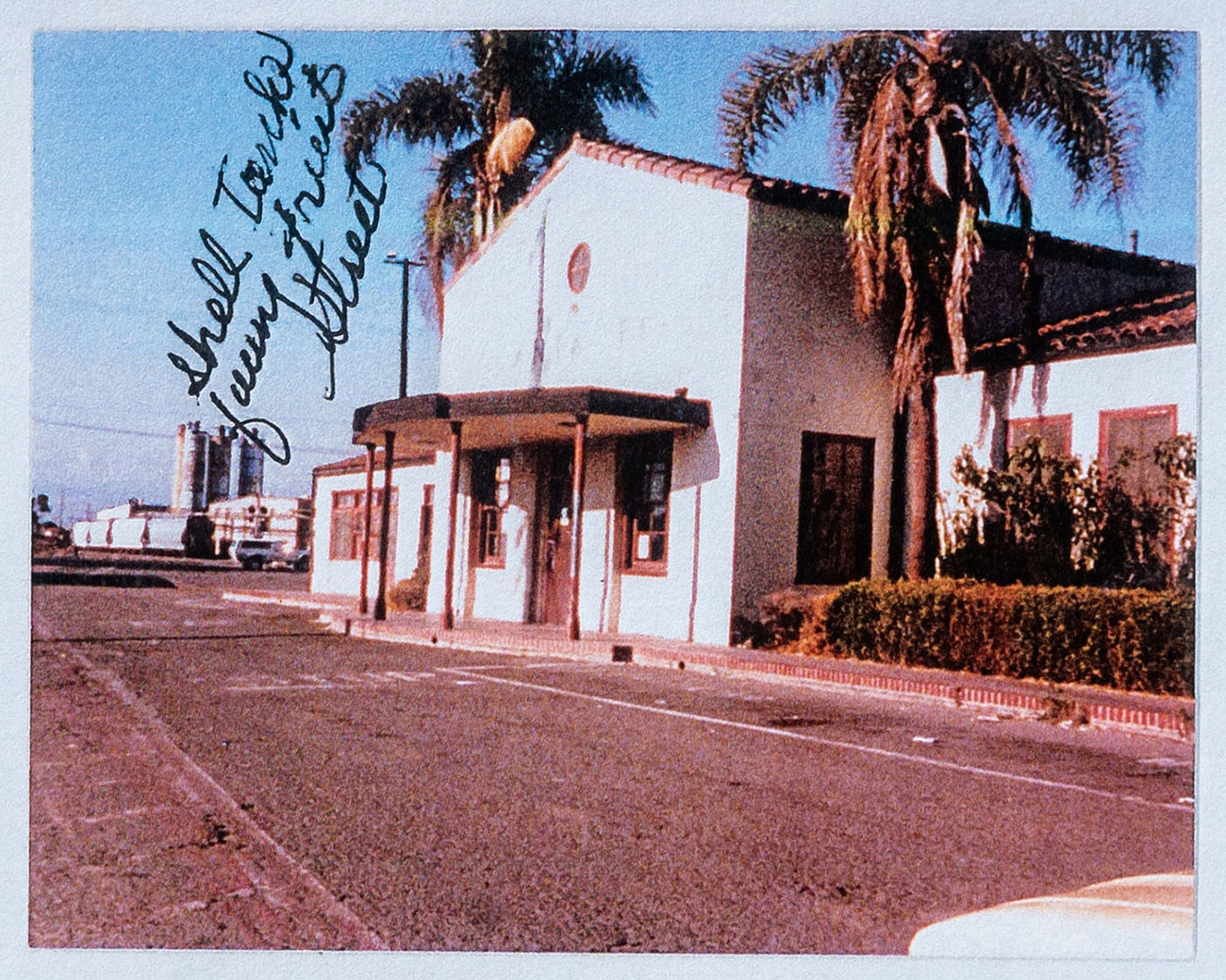

While neighborhoods on the city’s eastside, like the Greater Logan Area, have housed facilities such as a foundry and lead smelter in decades past, today the area is primarily surrounded by small and medium-sized industrial and commercial businesses. As recently as 1984, massive Shell oil tanks, like the ones from Garcia’s childhood, loomed over what is now Santa Ana Boulevard near the original Santa Fe railroad depot. Part of that area was paved over to make way for a parking lot for the Santa Ana Regional Transportation Center. The parcel where Sun Battery once manufactured batteries is now an auto wrecking lot, a cemetery of mangled car skeletons. Add to those potential hazards Santa Ana Boulevard, which bisects the Greater Logan Area and every day carries a stream of suburban commuters from nearby Interstate 5 headed into downtown — bringing with them dirty air and toxic exhaust from cars and trucks.

Each business in Logan has its own unique history: For example, the Shell Oil yard, which Orange County property records show operated from 1932 to at least 1976, included a warehouse, gasoline storage tanks, outbuildings, and a railroad connection to the Southern Pacific tracks. In 1942, a fire started by static electricity while a truck was being loaded swept through the warehouse, causing an estimated $4,000 to $5,000 in damages and endangered “scores of 50-gallon barrels of high-test aviation gasoline,” according to an article in the Santa Ana Register, now known as the Orange County Register. The story also noted that the property had seven 20,000- to 25,000-gallon stationary fuel tanks.

In the late-1940s, Sun Battery began making lead acid storage batteries (used for cars and marine storage) near the present-day train depot. The California manufacturing directories show that as the company grew to employ hundreds of workers, its property parcel expanded. In the 1950s, it also went by the name of the Lippincott Lead Company, which produced lead and lead alloys. A Sanborn map from this era notes that one of its buildings was dedicated to “battery lead melting.” According to National Park Service history documents, the company’s owner, George Lippincott, had another company mining for lead, silver, and zinc in the Lippincott “Lead King” Mine in Death Valley. The same records show that, in the early 1950s, the company erected a blast furnace operation in Santa Ana, where lead and silver were smelted for use in storage batteries. It’s unclear when the facility ceased operations: The directories confirm it operated as late as 1972 (when it had 400 employees), but it appears to have shuttered during the following decade.

What kind of mess the operation might have left in its wake — at the time that Sun Battery opened there were no federal regulations requiring monitoring of its emissions — has not been documented, until now. Grist sampled soil outside the gate of the former Sun Battery address in 2019. An XRF analyzer, which produces X-rays to measure the lead content of soil, found one lead level as high as 1,935 parts per million — more than six times the soil screening level for lead in industrial and commercial areas set by the state of California. RJ Lee Group Inc., a Pennsylvania-based industrial forensics analytical laboratory and scientific consulting firm, found that that sample contained high concentrations of two types of lead, with no direct evidence of automotive leaded gasoline contributions. (However, there was evidence of lead phosphate in the sample, which is a degraded byproduct of automotive lead.) The analysis — conducted by computer-controlled scanning electron microscopy, a method that collects images and a chemistry profile of individual particles — concluded that one of the likely sources of some of these particles was an industrial process using lead.

RJ Lee Group analyzed an additional four samples from the east side neighborhoods where Grist found the highest lead soil levels (Logan, French Park, and Lacy) and confirmed that, of the five samples, the highest lead concentrations were found near the former Sun Battery property. The firm is in the process of conducting a deeper analysis, but its initial findings suggest that the battery facility emissions appear to dominate in four of the five samples. The sources in the other samples vary: One sample taken from the yard of an older painted home contained lead barium, which is likely associated with lead paint. Others contained lead phosphate, which could come from multiple sources, including car exhaust.

Not much is known about the extent that Sun Battery’s operations might have polluted the surrounding soil in Logan, but an example just north of Santa Ana in Los Angeles County illustrates how, even during an era when regulations exist to monitor lead smelters, the environment around these facilities can become heavily contaminated. Researchers Jill Johnston and Andrea Hricko of the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine found that, in the decades after Exide began recycling batteries at the site in the late 1970s, public agencies failed to protect the predominantly Latino communities surrounding the smelter.

The researchers noted that it wasn’t until the community exerted pressure on the state Department of Toxic Substances Control that the agency conceded that Exide’s pollution could extend at least 1.7 miles from the facility. In their 2017 study, Johnston and Hricko pointed to soil data suggesting that 99 percent of properties within that area had lead concentrations that exceeded 80 parts per million, the level that the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment considers dangerous for children in residential areas.

The work of scientists across the country has shown exactly how pervasive soil lead contamination is in urban centers. Mark Laidlaw, a geologist and environmental scientist, has conducted extensive studies on lead exposure in the United States that have shown that soils in older urban areas remain highly contaminated by lead due largely to the use of leaded gasoline and paint in decades past, as well as industrial sources. Multiple studies have shown seasonal spikes in children’s blood lead levels in the summer and fall — meaning the problem extends beyond common culprits like leaded paint. Researchers have found this particularly in older, inner city areas where decades of accumulated lead in surface soils have produced lead hot spots. This lead is then reintroduced into the atmosphere as soil dust. While the amount of lead deposited in the soil of each city will vary depending on vehicle traffic, the age of its housing stock, and its industrial history, Laidlaw said that these soils remain a major source of blood lead poisoning, particularly for children.

A child plays in the dirt during a groundbreaking construction ceremony for Santa Ana’s Pacific Electric Park. Daniel A. Anderson

A child plays in the dirt during a groundbreaking construction ceremony for Santa Ana’s Pacific Electric Park. Daniel A. AndersonDespite overwhelming evidence, little has been done at the federal level to address this source of childhood lead exposure, said Laidlaw, a former researcher in the Centre for Environmental Sustainability and Remediation at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, who now works as an environmental consultant. “I think it’s just awareness,” he said. “I think a lot of this has been buried in academic journals.”

The problem is that most people forget that the very ground they walk on has become an invisible sink that catches the urban industrial waste of cities as land is bought, sold, and resold for different uses, Frickel and Elliott found. “Cities are always changing; that’s just what cities do,” said Frickel. “The question is how do we keep track of those changes especially when those changes present risks that may accumulate and continue to pose dangers to people decades after the activities that created them have gone away and are no longer visible or remembered.”

The perils of not knowing the industrial past of an urban environment can come at a steep cost for working-class communities and communities of color that are often living in areas where environmental hazards have existed for decades. According to California State University, Fullerton, Professor Erualdo González, an urban and regional planning expert who has studied the effects of redevelopment in Santa Ana’s urban core, tackling the toxic byproducts of formerly polluting industries in these neighborhoods has usually taken a backseat to more immediate needs such as affordable housing, addressing immigration status, or tackling threats such as the construction of new polluting facilities. “Environmental justice is oftentimes, in communities like [Logan], it’s historical things that have happened and persist, and it’s a harder battle,” said González, author of the 2017 book Latino City: Urban Planning, Politics, and the Grassroots.

Two studies examining levels of soil lead contamination in New York City have confirmed the risks faced by residents who live near former industrial sites. One 2018 study created the first comprehensive map of soil lead in the city, finding the highest levels in its oldest sections, which tend to be areas that are industrial and have seen heavy vehicle traffic. A second study published in 2020 focused on determining the lead contamination risks faced by residents in areas undergoing population growth, as well as land use changes — such as the redevelopment of land originally zoned for industry and manufacturing. It found that median concentrations of soil lead — and the rates of young children with elevated blood lead levels — were twice as high in redeveloped areas with a history of industrial and manufacturing land use, polluting facilities, and more roadways.

Santa Ana resident Idalia Rios walks her son to school in fall 2018, past a dirt lot that remained empty for years. Daniel A. Anderson

Santa Ana resident Idalia Rios walks her son to school in fall 2018, past a dirt lot that remained empty for years. Daniel A. AndersonJuliana Maantay, a professor of urban environmental geography at the City University of New York’s Lehman College, identified an inverted variation on that process, in which residential neighborhoods are rezoned to allow industry and manufacturing to creep in, such as Logan in Santa Ana. Maantay found that over a nearly four-decade period in the last half of the 20th century, rezoning actually concentrated industry in New York City neighborhoods where residents have less political clout, particularly communities of color and low-income areas. She’s found that neighborhoods were often zoned to increase industrial activity after they became poorer and more ethnically and racially diverse than the city itself. “In New York, as my research has shown, the likelihood of living near these noxious facilities, these polluting facilities, drastically increases with a population that’s more Black and Hispanic, and that is incontrovertible,” Maantay told Grist.

Even as cities across the country, including New York City, have de-industrialized, the footprint left behind by toxic facilities remains a danger to residents. “What’s not usually taken into account,” Maantay said, “is all these ghost facilities that are quite often still a source of contamination even though the facility may have closed a decade or two ago – so this is something that is quite worrisome.”

In the Bronx — the part of New York City that has had the highest number of manufacturing zone additions between 1961 and 1998 — the cumulative effects of many small businesses, even seemingly innocuous enterprises such as dry cleaners and auto body shops, have had a devastating impact on residents, according to Maantay. “When you add them all together, if there’s many of them in the neighborhood, it can be very deleterious,” she said, reiterating that small industrial operations don’t receive the same regulatory scrutiny as large ones.

As far as what can be done to address the long-term health effects, Maantay recommends adopting what’s known as the “precautionary principle”: Even in the absence of cause-and-effect scientific evidence linking residents’ health problems to industrial activity, cities should still work to improve conditions in the most environmentally-burdened neighborhoods. The challenge for cities is addressing the problem without displacing residents, she said. “We know how to do the cleanups — it’s expensive, but we know how to do it,” Maantay said. “But the trick is, how do we do it without harming the people that are already being harmed?”

Carmen Lopez Padilla peers into a Logan industrial business on Lincoln Avenue, where she was born and raised. A residential home borders the business. Daniel A. Anderson

Carmen Lopez Padilla peers into a Logan industrial business on Lincoln Avenue, where she was born and raised. A residential home borders the business. Daniel A. AndersonIn 2020, a coalition of Santa Ana residents, advocates, and academic scholars published a study highlighting how children in Santa Ana’s poorest areas are at a higher risk of being exposed to lead soil contamination. Last year, the coalition released additional research, a risk assessment of eight toxic heavy metals from the initial soil study. It found that census tracts where the median household income was under $50,000 had higher concentrations of lead, arsenic, zinc, and cadmium compared to high-income tracts. The analysis also found that tracts with a greater proportion of children, renters, residents lacking health insurance coverage, and fewer college-educated residents had higher average lead and zinc levels. The tracts with a greater proportion of non-native residents, who spoke limited English, and identified as Latino, also had much higher concentrations of these metals than other census tracts, with the researchers finding a similar pattern for arsenic and cadmium.

The findings indicate that a greater number of Santa Ana residents are likely to be exposed to lead, which has irreversible developmental effects on a child’s brain, and a smaller group of residents are at higher risk of being exposed to potentially cancer-causing chemicals like arsenic. Shahir Masri, who co-authored the study, told Grist that the findings indicate how pervasive the health risks are, particularly for vulnerable populations.

“I think it just makes for a further case as to why we need to remediate the soil,” said Masri, an assistant specialist in air pollution exposure assessment and epidemiology at the University of California, Irvine.

In Santa Ana’s Logan barrio, where generations of residents have fought to keep industrialization at bay, Garcia said she is proud that the neighborhood still has the spirit she cherishes from her childhood. The people, and their pride in what Logan represented — a place to call home for all who traveled through — have kept the barrio alive. It’s a neighborhood where family ties and friendship have survived despite the challenges of World War II, repatriations to Mexico, segregation, and battles over civil rights. “It was pride, that — even though we didn’t have a lot of money — what we did have, it was through hard work and struggles,” said Garcia, who now lives nearby in the city of Orange.

Mary Garcia, left, with her brother Henry, center, and cousin Olga, right, standing in front of her grandfather’s garage in the Logan barrio. Photograph courtesy of Mary Garcia

Mary Garcia, left, with her brother Henry, center, and cousin Olga, right, standing in front of her grandfather’s garage in the Logan barrio. Photograph courtesy of Mary GarciaThe homegrown businesses that thrived during her childhood have long vanished: The tortillería, the tamalería, the corner grocery market, the barbershop, and the shoe repair shop are gone. But as she makes her way through the barrio, Garcia recalls the sticky sweetness of the oranges the local grocer would freeze for the neighborhood children. Her mind takes her back in time to the days when the Santa Ana winds would howl through the streets, when the trains would thunder through the barrio, and when she’d walk along the railroad tracks with her cousins seeking adventures.

As new families move into the neighborhood, she wonders if they know how hard the generations before them have fought to preserve that Logan spirit. “I hope,” said Garcia, “that they recognize that it took a lot to get even where the Logan barrio is right now.”

–

Reporter Uriel Garcia contributed to this story.

This story was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York. This report was also made possible in part by the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists, and by the Kozik Challenge Grants funded by the National Press Foundation and the National Press Club Journalism Institute.

A special thank you to Orange County Archivist Susan Berumen, Assistant Archivist Chris Jepsen, and Digital Archives Specialist Steve Ofteli, as well as the staff of the Santa Ana Public Library History Room, Vermont Law School’s Cornell Library, and the Sherman Library & Gardens in Corona del Mar for their expertise and assistance in archival research. The Josephine Andrade oral history interview is provided courtesy of the Lawrence De Graaf Center for Oral and Public History at California State University, Fullerton. The soil testing was made possible thanks to the generosity of Thermo Fisher Scientific, which provided an XRF analyzer on loan to conduct soil testing for this investigation.